Home A-Z A-Z text British German Unidentified Reprint Birth Sunday Chronological

The Birth of Modern Comics (1800-1860)

|

Modern comics, with a storytelling vocabulary that's still used today, were developed in America's newspaper strips, circa 1900-1920. They were mostly following a tradition of short, colourful picture-stories for children. The direct influence was the slapstick work by Wilhelm Busch and others in a similar vein. But that in turn was built on a sixty year (or more) tradition of children's comics.

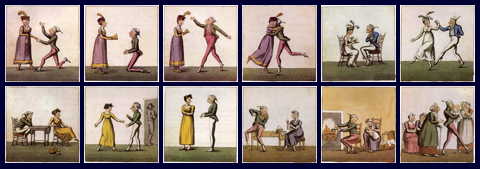

Busch started working in 1859, for a series of picture broadsheets called 'Münchner Bilderbogen' (See below, or click here for examples), which had been going since 1849, a series which included many inventive and sumptiously illustrated comics from the start. These were themselves influenced by the charmingly naive 'Neuruppiner Bilderbogen', which started producing comic-like picture stories in 1835. And those again were influenced by British chapbooks with comic-like picture stories, starting around 1800. Even earlier were precursors in Holland. Below are a number of examples, in case you think I'm making this all up. First two very early examples from Holland. It seems that although the Dutch had the most spectacular fall in artistic relevance around 1700, there still was an important tradition of printmaking, and highly important for the development of comics. |

|

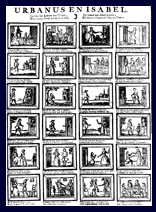

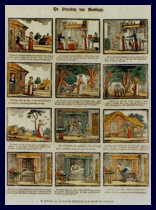

Urbanus and Isabel Dutch Broadsheet (circa 1750) They marry. He goes off whoring. She divorces him. Years later he comes crawling back and she is overjoyed to take him back and all is well. Maybe this one wasn't a childrens story yet (although you never know with the Dutch), but the next one is.  Little Red Ridinghood Dutch Broadsheet (1800) by G. Oortmann, publisher: by de Erve H. Rynders - earliest Dutch broadsheet after Perrault. This predates the famous Grimm's version by 11 years.  |

|

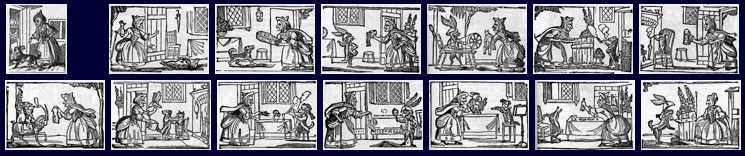

From around 1800 the most important country for comics is England. Here stories told in pictures turn up inside chap-books.

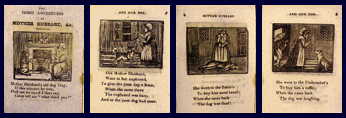

Chapbooks were small booklets of four, (or multiples of four: 8, 12,...) pages, and sold by itinerant merchants or chapmen (Old English: ceapman from 'ceap' - bargaining, trade) from the 16th to the early 19th century. They were illustrated with woodcuts and had stories of popular heroes, folklore, famous crimes, ballads, nursery rhymes, schooltexts (ABCs), bible tales, etc, and were the main literature beside the bible for the common man and children.

They too were sometimes sold as sheets which had to be cut up and bound, DIY-fashion.

Most chapbooks were not comics of course, but enough of them were to constitute a genuine and influential tradition. Some of the examples below are from American edtions. I'm not sure if these were reprints, copies or original. |

|

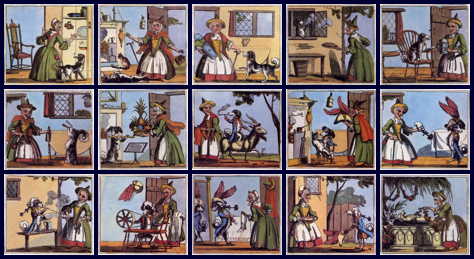

The Little Man & the Little Maid (1807)  The Comical Adventures of the Little Woman, Her Dog and the Pedlar (1820s) printed in Baltimore, by William Raint  Robert Branston Old Mother Hubbard and her Dog - Various early editions including a lovely one from 1819, probably by Robert Branston    Robert Branston 'The Comical Cat' (1818) Another 'Madam with an animal' thingy by Branston, plus a couple of later US variations.    Robert Branston Dame Wiggins of Lee and her Seven Wonderful Cats (1823) More an illustrated story than a comic, because not enough of the relevant action is shown visually. This was a favourite childrens book of the art critic John Ruskin.  Grandmamma Easy's Old Dame Hicket and Her Wonderful Cricket (circa 1840) Boston: Brown, Bazin & Co. Nashua, N.H.: N.P Greene & Co.  There are a lot more of these wacky old-Mother-this-Grandma-that picture books. Below examples of more conventional 19th century stories. The Two Sisters (circa 1825) From The Pretty Primer (The Juvenile Gem), Huestis & Cozans, 104 Nassau Street, New York  The Story of Little Sarah and Her Johnny-Cake (circa 1830) Boston: W.J.Reynolds & Co.  The Children in the Wood (circa 1825) published by Dunigan, New York  Adventures of Little Red Riding Hood (circa 1820) Mark's Edition - Published by Fisk & Little, 82 State-Street, Albany, New York  |

|

These chapbooks had an important influence on the next stage of mass-market comics for children.

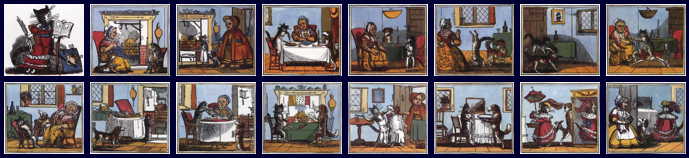

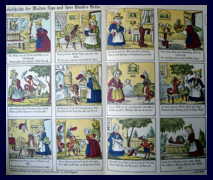

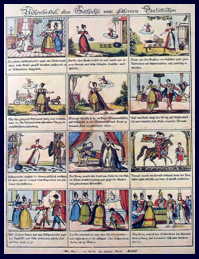

In the mid 1830s the little town of Neuruppin, north of Berlin, became an important centre for picture sheets. A good number of these were comics. Below are a few early examples.

Later on, in 1848, these Neuruppiner Bilderbogen themselves influenced the more sophisticated 'Münchner Bilderbogen' (Munich picture broadsheets), where in 1859 the great Wilhelm Busch started his own brand of picture stories, which would influence cartoonists all over the world, and eventually the Sunday supplement comics. In other words, there is a direct line of influence from the Dutch broadsheets/ English chapbooks to 20th century comics. |

|

Geschichte der Madam Rips und ihres Hundes Bello 1835/40 This sheet demonstrates the international influence of British picture stories - a close copy of Old Hubbard, translated into German: (the English version was here) . Bello comes from 'bellen', to bark. Typical doggie name.

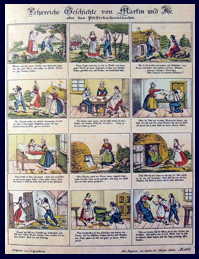

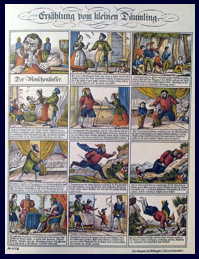

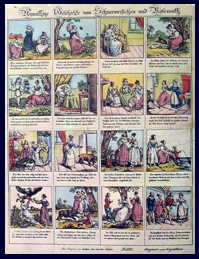

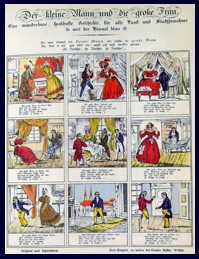

More common were these charming fairy tale adaptations: Cinderella 1835/40  Hansel and Gretel (here called Martin and Ilse) 1835/40  Erzählung vom kleinen Däumling / Story about Little Tom Thumb (1835/40)  Schneeweisschen und Rosenrot (1835/40) (Little Snowwhite and Rosered) (not the Snowwhite, who is called 'Schneewittchen' in German)  There were also popular stories of romantic robbers: Rinaldo Rinaldini (1835/40) ...  ...or a satire for grown-ups about emancipated women (and why to avoid them): Der Kleine Mann und die grosse Frau (The little Man and the large Woman) (1835/40)  Heinrich Hoffmann 'Struwwelpeter' (drawn 1844, published 1847 - English edition 1848) This famous picture book is stylistically related to earlier chapbooks and Bilderbogen / picture broad sheets. The hunter/rabbit story is similar to a panel from an earlier Bilderbogen showing (non-sequential) instances of a 'topsy turvy' world.  |

Copyright © 2011 by Andy Konky Kru

Home